Introduction

The Taiwan International Human Rights Film Festival (TIHRFF), an annual event that has become a cornerstone of Taiwan's vibrant cultural landscape, once again opened its doors to the public this September. Hosted by the National Human Rights Museum at the iconic Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, the festival has, for years, served as a platform to shed light on critical human rights issues from around the globe. This year’s theme focuses on the connection between sustainability and human rights, promising a compelling lineup of films that explore the intricate and often fraught human relationships between both ourselves and the planet. Through several of its showcased films, the festival aims to foster a deeper understanding of how environmental degradation, climate change, and the exploitation of natural resources are not just ecological crises but also pressing human rights concerns.

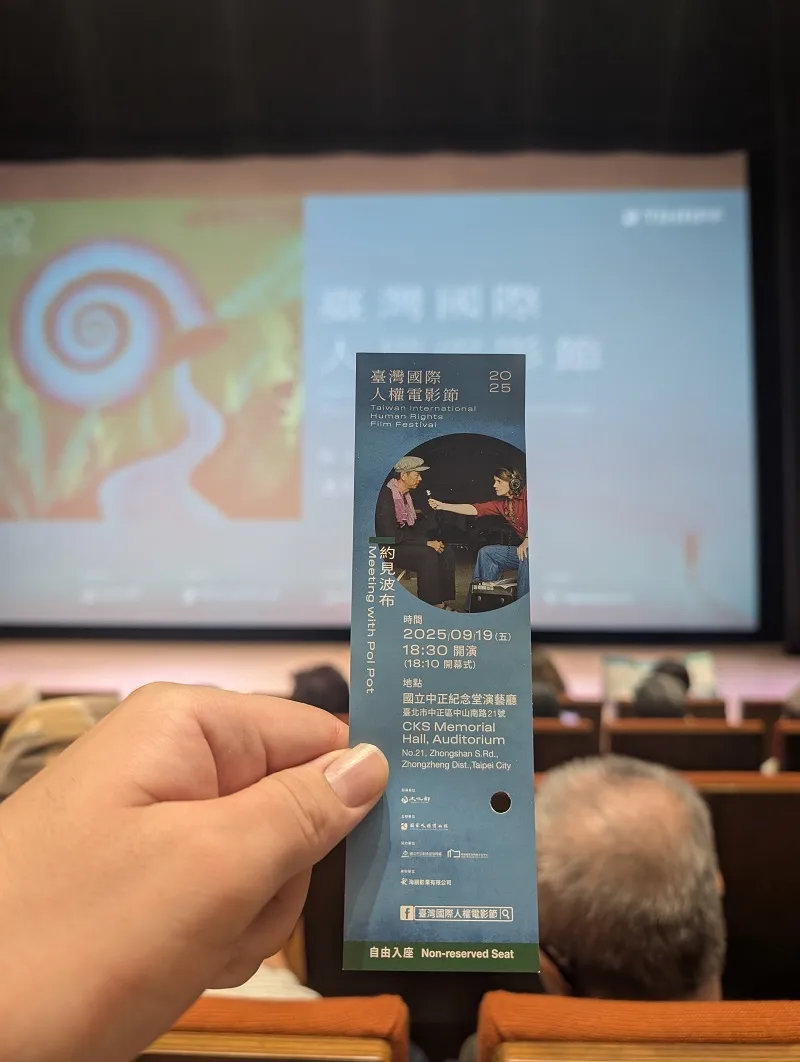

The opening night set the stage for a month of powerful and thought-provoking cinema. The evening commenced with a palpable sense of anticipation during the opening reception, a tension which culminated in the screening of the festival’s opening film: “Meeting with Pol Pot”. The selection of this film, a haunting and unflinching look into the heart of one of history’s most brutal regimes, underscores the festival’s commitment to exploring the depth of tragedy that occurs in the absence of human rights. It is a harrowing tale directed by a survivor of the very horrors it depicts, using a unique and surreal artistic style to confront the past. The film reminds us that the abuse of power with the blind consent of the public, in any form, ultimately leads to the degradation of both human life and the world we inhabit.

▲Three of NCCU's IMAS students enjoying a quick laugh before the festival

The Opening Reception

I was lucky to receive an invitation to the opening reception from a connection of mine in the local community, something that was extended to several students of NCCU. As we approached the towering Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, I couldn’t help but feel the sense of power that resulted from holding such an event in this mythical place. Debates have raged in Taiwan over the legacy of Chiang’s 25 years of authoritarian rule, and thus I could think of no better venue for such an event. In fact, as we prepared to enter the building, a group of honor guards were marching their way out to relieve their compatriots standing guard in front of the massive statue above.

The event’s first hour involved a great deal of wine and hors d'oeuvres, which the crowd gladly partook in. The same connection who invited me to this prestigious event also made it possible for me to meet several key figures, including one of the organizers, the director of the United States’ cultural exchange program, Fulbright, and the director of the film himself, Rithy Panh. The walls of the reception area were covered in photographs of famous moments in the history of human rights in Taiwan. It was awe-inspiring to see the work of prior generations on the wall before me, inviting me to contemplate the complexities it presented, preparing my mind for the film to come.

▲Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall served as a powerful and poignant venue for the film festival

The Cambodian Genocide and the Khmer Rouge

To fully grasp the film’s chilling reality, it’s essential to understand its historical context. The Khmer Rouge, a radical communist movement led by Pol Pot, seized control of Cambodia in 1975. In their fanatical attempt to create a utopian agrarian society, they immediately evacuated the cities, forcing millions into the countryside to work as slaves. The regime declared “Year Zero”, systematically dismantling family, religion, and culture. Intellectuals, artists, and anyone deemed an enemy of the revolution were targeted for execution in the infamous “killing fields”. In this period, simply wearing glasses could get you targeted by the regime.

Over four years, an estimated two million people—a quarter of the country’s population—died from starvation, disease, overwork, and murder. It is a history that director Rithy Panh knows not from books, but from personal experience. His film is a searing reminder of the consequences of unchecked power and the world’s failure to intervene. It stands as a testament to those who perished and a powerful counter-narrative to the propaganda and genocide denial that persisted for years in Cambodia after the regime’s fall.

The Film: “Meeting with Pol Pot”

The film, “Meeting with Pol Pot” (original French title: “Rendez-vous avec Pol Pot”), is a 2024 drama that unfolds like a historical horror film. Directed by the acclaimed Rithy Panh, it is a fictionalized account based on the chilling memoir “When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution” by journalist Elizabeth Becker. It recounts her real-life experience as one of three Western journalists granted a rare interview in 1978 with the enigmatic and brutal leader of the Khmer Rouge.

The film follows three French journalists—Lise Delbo (Irène Jacob), Paul Thomas (Cyril Gueï), and the Marxist idealist Alain Cariou (Grégoire Colin)—who are invited to Democratic Kampuchea. They arrive in a country that appears to be a pastoral paradise, a meticulously constructed deception. However, as their guided tour continues, the beautiful façade begins to crumble, revealing the horrifying reality of a nation in the grip of a genocidal regime.

▲The director of the film, Rithy Panh (center), sits for a panel after the screening

Panh masterfully builds a surreal and disassociated atmosphere, shifting the tone from cultural exchange to paranoid thriller and, finally, to outright horror. The journalists’ journey becomes a claustrophobic descent into darkness, their every move monitored by smiling but sinister handlers. As they witness the fear behind the citizens’ eyes and the hollowness of the regime’s propaganda, their quest for truth slowly becomes a perilous endeavor. That is not to say that the film is scary in a traditional sense; instead, it shocks the viewer with the hideous truth. Reels of actual historical footage play multiple times throughout the film, jabbing the audience periodically as if to say “Yes, this actually happened”. And in that sense, the director never lets the audience get too comfortable in the notion that they are observing a ‘fictional’ story.

What makes the film so profoundly unsettling is Panh’s signature cinematic style. He powerfully blends the dramatic reenactments with this black-and-white archival footage of forced labor, death, and torture. In a technique he famously used in his Oscar-nominated documentary “The Missing Picture”, Panh also utilizes miniature clay figurines and elaborate dioramas to depict events that were never documented, or perhaps, are too horrible to process as reality. This juxtaposition of the real and the constructed creates a deeply intimate and disturbing experience, reflecting the psychological trauma of the era. As the viewer, we, disturbingly, want to see what happened in these diorama moments, and ultimately find ourselves grappling with asking ourselves ‘why’ we want to see more of this horror.

The Director: A Survivor’s Testimony

To understand the profound weight of “Meeting with Pol Pot”, one must understand the man who created it. In conducting research for this article, I found an article in the Los Angeles Times by Robert Abele to be very revealing. Rithy Panh is not just a director; he is a survivor. As a child, he and his family were expelled from Phnom Penh, and he spent years in the Khmer Rouge’s brutal labor camps, where he lost his parents and siblings to starvation and exhaustion. After escaping to a refugee camp in Thailand, he eventually made his way to Paris, where he studied film.

Panh has dedicated his life and career to bearing witness and ensuring the Cambodian genocide is never forgotten. His body of work, including landmark documentaries like “S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine”, which confronts former prison guards with their past, serves as a form of public memory. His films are not those of a hobbyist or a historian; Panh himself lived, in essence, many of the moments he depicts. This painful intimacy is his work’s greatest strength. It seems that “Meeting with Pol Pot” is the culmination of this lifelong project, exploring the willful ignorance of Western sympathizers and the chilling, logical conclusion of a pure, anti-human ideology.

▲When invited to an event like this, be sure to always sample the free food and beverages!

Reflecting on the Film and Conclusion

Walking out of the theater and back into the humid Taipei night, I found myself grappling with a profound sense of unease, but also a deep and abiding gratitude. It’s not often that a film leaves you shaken, but “Meeting with Pol Pot” did exactly that. The director’s unflinching gaze forces you to confront the darkest capabilities of humanity, and I was left incredibly thankful that artists like Rithy Panh exist to bear witness and that institutions like the National Human Rights Museum here in Taiwan have the courage to showcase their work.

My main takeaway from the evening is that human rights are not a given; they are a collective societal effort. The horrors on display in the film—the “killing fields”, the systematic erasure of culture, the starvation—were not the actions of one man, but the result of a national project. Such atrocities are only made possible by the explicit or implicit consent of a populace, whether that consent is extracted through fear, cultivated through hatred, or twisted by a false sense of revolutionary justice. This film is a terrifying reminder that the guardrails of civilization can be dismantled when ordinary people are convinced to look the other way or, worse, to participate.

▲Meeting with Pol Pot" was the opening film for the festival

Here in Taiwan, a place that has navigated its own difficult path towards peace and human rights, this lesson feels especially potent. We must never forget that these concepts are fragile. They require our constant vigilance, our empathy, and our willingness to speak out against injustice, lest we too fall silent. The annual Taiwan International Human Rights Film Festival is more than just a collection of movies; it's a vital part of that vigilance, a space for the community to come together, to remember, and to reaffirm its commitment to a better future.