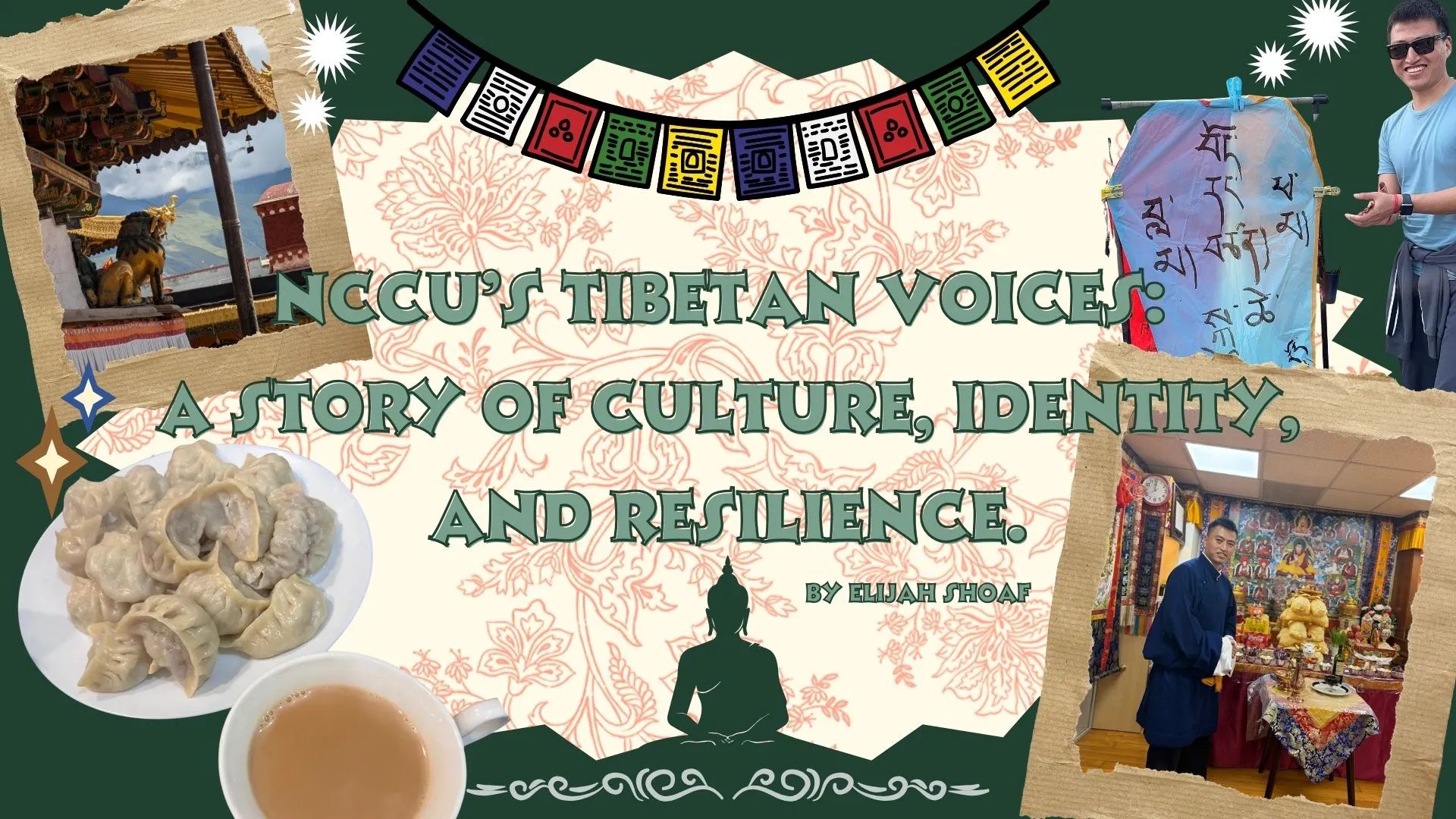

Among the thousands of students walking the campus of National Chengchi University, every face holds a unique story. But some stories carry the weight of nations, histories, and journeys that stretch far beyond the typical student experience. This is the case for Norbu, a second-year IMAS student, and Tenzin Namdol Rinpoche, a revered Buddhist teacher pursuing a PhD in Buddhist philosophy here at NCCU. They are members of Taiwan's Tibetan community, and their stories offer a profound look into the complexities of culture, identity, and the search for home.

For both students, Taiwan has become a place of opportunity and safety. It is a society they describe as overwhelmingly friendly to foreigners, safe, and convenient. Crucially, it is a place where they feel free to be themselves and openly express their vibrant culture. This sense of welcome was one of the first things Norbu noticed. His biggest culture shock upon arriving was the sheer politeness of the society here. Upon arriving, he found the contrast stark, particularly when comparing it to his past experiences with government officials, who, in his words, typically "do not treat people well" when compared to those in Taiwan.

▲Tibetans in Taiwan are free to practice their culture and religion

However, settling into academic and social life comes with its own set of hurdles. The most immediate is the language barrier. Both Norbu and Rinpoche agree that while it's possible to get by with English among the younger population, learning Mandarin is essential to truly connect with the local people and culture. This reflects the experience of many of the international students at NCCU; learning the local language, whether Taiwanese or Mandarin, will open up new avenues for exploration you never imagined to be possible!

Beyond language, a more systemic and fascinating academic challenge exists. In Tibetan culture, lamas (teachers) hold monastery degrees that are considered equivalent to traditional university degrees like a Master's or PhD. While these qualifications are recognized in countries like the United States, they are not formally recognized within Taiwan's system. This gap can create significant obstacles for Tibetan scholars and religious leaders seeking to have their extensive education and expertise acknowledged in their new academic environment. Ultimately, however, individual pathways were able to be opened up which allows well-educated thinkers like the Rinpoche to pursue advanced education here in Taiwan.

They both also shared that life in Taipei offers vibrant, and sometimes complex, opportunities for cultural exchange. This can be best understood through the diversity of culinary traditions found in the area. For those seeking a taste of the Himalayas, Tibetan cuisine can be found in the city at restaurants like the popular "Tibetan Kitchen" in Da'an. Norbu remarked that he often spends his weekends at Tibetan religious centers, where he can cook traditional dishes like momo (dumplings traditionally made with yak meat) and tentunk (a special noodle soup consumed often in winter as a comfort food) alongside boiled meat so tender it falls off the bone.

▲Momo (yak dumplings) with traditional Tibetan butter tea

Yet, he has also wholeheartedly embraced the local flavors, citing Taiwanese beef noodles and the wide variety of local dumplings as his favorite dishes to enjoy at night markets. When Tibetan and Taiwanese Buddhists meet, however, points of culinary friction are revealed. The traditional Tibetan diet is rich in meat, a necessity in the high-altitude environment of Tibet where yaks are plentiful and edible plants are scarce. This stands in contrast to the practices of many Taiwanese Buddhists, who adhere to strict vegetarian diets. This dietary difference can sometimes be a source of misunderstanding or friction between the two communities, showcasing a perfect example of how Taiwan often acts as a cultural melting pot.

Maintaining and sharing Tibetan heritage is a constant and personal endeavor within their diaspora. Deeply important to the Tibetan people, their culture is often shared through lively festivals filled with dancing, singing, prayer, and teaching, as well as through performances by touring cultural troupes that bring their tapestry of traditions to the people of Taiwan. Despite these efforts, the largest obstacle to cultural preservation in Taiwan is the lack of robust Tibetan language programs. For those wishing to study their mother tongue, the options are few and largely confined to Taipei.

Beyond the daily challenges of academic life and cultural preservation lies a more profound and defining reality for many Tibetans in Taiwan: they are stateless. Norbu's experience is fundamentally unique because he is a refugee and, therefore, has no official nationality. The Rinpoche shares this reality and speaks to its deep emotional weight. He expressed that his greatest desire is to have his own country and the freedom given by a passport—one of the most basic benefits of statehood that is often taken for granted.

This status can also create immense practical and bureaucratic challenges. There is currently no formal framework or visa category for stateless people like Tibetan refugees to come to Taiwan for their studies. As a result, many are forced to rely on temporary visitor's visas, living with uncertainty about their future. In a testament to the difficulty of their situation, Norbu and the Rinpoche are among the only ones in their community who have managed to secure official residence status.

▲Norbu's experience (as pictured here) has been a constant mixture of Taiwanese and Tibetan culture

Despite these immense personal and systemic struggles, what shines through is a powerful story of resilience and connection. The Rinpoche, through his role as a lama and spiritual teacher, has forged a deep and special bond with the Taiwanese people. He teaches Buddhist classes, often to very young locals, creating a space for open dialogue and support. In these classes, students often feel comfortable enough to share their deepest personal issues, including their struggles with the ongoing mental health crisis affecting many young people today. In this exchange, the Rinpoche is not just a teacher of philosophy but a pillar of support for his new community, building bridges of understanding and compassion that transcend culture and nationality.

To hear these stories while living in Taiwan is to experience a powerful sense of resonance, as the struggles and aspirations of the Tibetan community echo themes that are deeply woven into the island's own narrative. The Rinpoche's deeply personal desires and discussions with local youth together transcend politics—they speak to a universal human need for a recognized home and for a place on the map that is undeniably one's own. This fundamental aspiration for self-determination and a distinct international identity is a conversation that reverberates daily across Taiwanese society, which continues to navigate its own complex geopolitical challenges and define its place in the world.

Similarly, the struggle to preserve a unique identity against overwhelming external forces is a familiar story here. The immense importance placed on Tibetan cultural heritage and the fight against its erosion, symbolized by the scarcity of robust Tibetan language programs, mirrors Taiwan's own multi-generational efforts to safeguard its distinct languages, diverse traditions, and democratic way of life. This shared experience creates an unspoken undercurrent of solidarity—a mutual understanding of what it means to protect a cherished identity from a powerful external narrative that seeks to absorb it.

Yet, the connection is not solely one of shared anxieties. It is perhaps most poignantly found in a shared commitment to freedom. The fact that both Norbu and the Rinpoche feel they can openly and freely express their culture here is a testament to Taiwan's evolution into a democratic sanctuary. It has become a place where the very freedoms that are sought after are actively practiced, creating a unique environment where a refugee community can find safety and solidarity in a society grappling with mounting an effective resistance against their own displacement. This complex interplay of shared struggle and shared values transforms the Tibetan experience in Taiwan from a simple story of diaspora into a profound reflection of the enduring fight for identity in the face of mainland Chinese narratives.

▲One site that all Tibetan refugees miss is their most holy site, Jokhang Temple (pictured)

The stories of Norbu and Tenzin Namdol Rinpoche are a vital part of the diverse community of NCCU. They are a testament to the human spirit's ability to seek knowledge and build community in the face of adversity. Their presence here enriches our campus, reminding us that behind every student is a story worth listening to—a story of challenges overcome, of cultures shared, and of the enduring hope for a place to truly call home.