By Montana Meeker

Introduction: How Do We Make Friends?

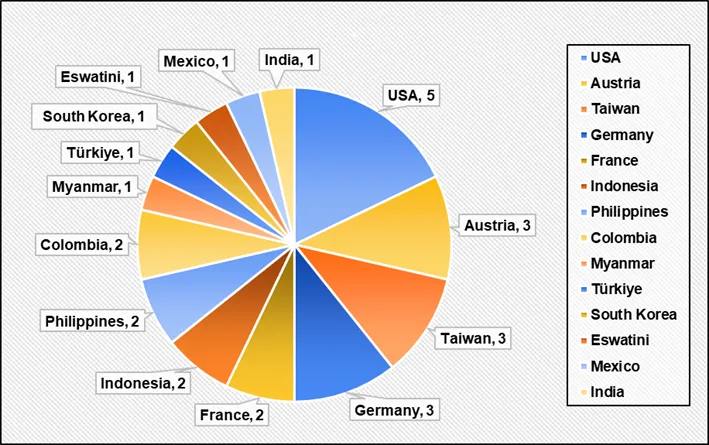

The combination of isolation and cultural “otherness” experienced abroad can create a new awareness of your background and cultural habits. For example, when I arrived in Taiwan to begin my graduate studies, I felt a strong pull to identify with my Texas roots and emphasize my belonging to my homeland in a way I hadn’t felt the urge to before. My classmates did something similar - French friends talked about conflicting dating norms, Filipino friends commented on differences in the local food, and other Americans made jokes about politicians back home. Seeing this made me question: what expectations and values for our friendships do we bring from our home cultures when we travel abroad? How do these contrasting cultural values influence friendships in NCCU's international community? To explore how cultural values shape friendships, I surveyed 28 NCCU students and one faculty member from 14 countries. While not a representative sample, the survey revealed some interesting insights into how the NCCU community connects across cultures. Figure 1 below displays the survey respondents by their country of origin.

Figure 1. Survey Respondents By Country

Meeting and Making Friends

When asked how they made friends, survey respondents said they met most of their friends at school or work (36%), followed by connections through mutual friends and family (27%), or through hobbies and religious or volunteer activities (26%). Just three people mentioned they had met friends online (11%). Beyond the initial meeting, students mentioned cultural factors that affected how they formed friendships, such as age, stereotypical habits, religious practices, and even the physical characteristics of their home country.

Hyeline Kang of the IMES program said: “In Korea, age is an important factor in forming friendships because of the country’s culture of formal speech and casual speech, so most friends are of the same age. People from other countries might find this confusing.”

Some students brought up stereotypes they found descriptive of their personal patterns in friendships. German student Leonard Kamke of the IMES program shared his experience as well: “Germans are [stereotyped as] lonely people that do not meet up with our friends often enough. In my experience, this is true: we do not make many friends, but the ones we do make become very close.”

Religious and ethnic ties were also important factors for students surveyed. Jasenghkawn Saga, an NCCU IMAS student from Myanmar, recounted the role of ethnicity and religion in her earliest deep friendships: “The [person] who sat in my Sunday school class became my best friend for over two decades; now we are family. In my country, ethnicity and religion play a very important role in making friends. We feel that sharing the same ethnicity and religion (sometimes even the same church), helps us connect and make friends more easily. Our ethnic bond and Christian bond make our friendship longer-lasting and help us understand each other better.”

▲NCCU IMAS Students Jasenghkawn Saga from Myanmar and Gemma from the USA

Even the geographic makeup of a country was mentioned as a potential aid to connection. Taiwanese local William Pan mentioned he believed that the island geography and transportation systems present in Taiwan facilitated quicker creation of friendships. “It’s a small island, so it is easy to bump into people and get to know them. People are friendly, and you tend to run into familiar faces wherever you go.”

How Long Does It Take To Make A Close Friend?

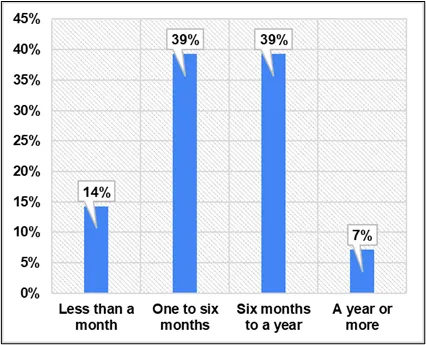

When asked how long it took on average to consider someone a close friend after meeting them, the majority of NCCU students shared that they felt they formed close friendships within six months of meeting a new person, and just 7% of students surveyed said it would take them more than a year to feel truly close to a new friend. But of course, the timeline to open up to new people can be different depending on the individual and their circumstances.

Florah Vixamar-Betton from France, of the NCCU IMES program, had the following to share about her experiences with different cultural timelines for friendship formation: “French people sometimes can be honest and direct to a level that others can perceive as rude - we will tell our friends directly what we think about their actions. French people are not "friendly" with strangers, we do not talk to people we don't know at work or in the streets. French people prefer to meet people through shared hobbies or friends of friends. Every culture has two circles, the public and private. In American culture, it is easier to get into someone's public circle, but it is really difficult to get into their private circle. In France it is the opposite. If you make it through the public circle (which is really difficult) you will very easily make it into someone's private circle. However, when I studied in Canada, I did not make close friends for the first nine months that I was there. I ate most meals alone, and that was pretty normal from what I saw. In three years in France, I never ate a meal alone. In Canada, I worried that no one liked me, but it was really just a cultural difference - it takes longer there to make friends.” As shown in Figure 2, most students said it takes six months or less to form a close friendship, though cultural timelines vary significantly.

Figure 2. How Long Does it Take to Consider Someone a Close Friend?

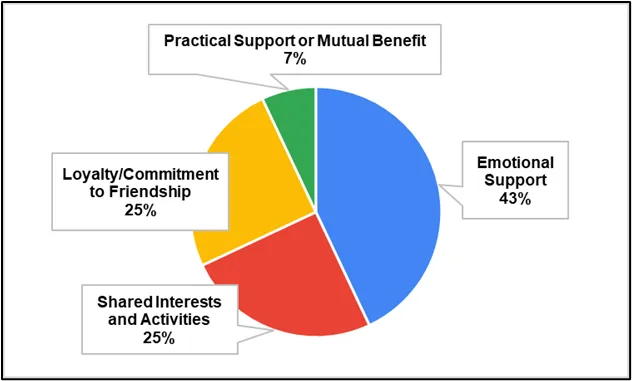

When it comes to what goes into making those friendships worthwhile, 43% of survey respondents said that mutual emotional support was the most important factor in a valuable friendship. Tied for second place were: loyalty and commitment to the friendship; and shared interests and activities. Only two people polled thought practical support or mutual benefit was most valuable in a friendship. Figure 3 shows what survey respondents mentioned they valued most in their friendships.

Figure 3. What Respondents Value Most in Friendships

Many students mentioned making new friends at NCCU was easier than at home due to the international campus environment and the presence of other foreign students in a similar stage of life. Daniel Gombos, an Austrian student in the IMAS program, shared his experience making friends at home in comparison to his time at NCCU. “Austria is individualistic, but I built my friend group [there] based on a desire from all the people involved to discuss political issues, which are very personal. I love them, but they are on the other side of the planet and we only talk maybe once a month. The friends I have made in Taiwan I talk to almost daily, [despite having known each other] for only two months. To me, place matters. [In Taiwan] I have a community where exchange is long, frequent, and keeps us up chatting past midnight on our dorm floor… In Austria, friend culture tends to be [centered] around drinking.”

Staying Connected With Friends

▲International student friends having fun in Taiwan

Once friendships form, maintaining them requires effort—though the ways people connect often depend on cultural norms. When asked how connections with friends were maintained over time, 50% of survey respondents preferred spending quality time with others as their primary way of connecting in friendships (notably, all respondents from the United States, Austria, and France marked this as their preferred method of connecting with friends). 32% of respondents mentioned that talking through text or social media was their preferred way of connecting with their friends, and 18% liked to show appreciation through acts of service.

When it came to how time was shared amongst one’s friends, there was a slight preference for group activities among the surveyed students. Students reported spending about 55% of their time with friends in a group setting. Most students reported taking care to maintain regular communication with people they considered good friends: 42% said they communicated with people they considered close friends either daily or almost daily. However, communication style and content preferences varied among respondents.

▲IMAS Student Danie Gombos with NCCU Friends

Irem Kepeefnek, a Turkish student in the IMAS program, shared her thoughts on communication as a Turkish person. “Turkish people care a lot about maintaining friendships and will put in the work to maintain friendships for a long time. We are very honest, but maybe less direct than the French. We beat around the bush a bit when we say what we think, and use a lot of niceties (like jokes or sarcasm) to gently make our point. We care about other people's emotions and how they will feel about what we say. Turkish people generally find small talk unnecessary - it sometimes feels fake when someone from a country that really enjoys small talk tries to make small talk with us. We don't like to be talked at or asked vague questions, but we do like when people ask purposeful things, so that we know we are truly cared about and considered. If we don’t know people well, we will exchange pleasantries, but we don't do small talk. It kind of shocks me to see that people from some cultures such as the U.S. will go and spend time with people they do not like or consider friends just to avoid being rude.”

Although the tendency of some countries (the United States) to over-engage in small talk received criticism during interviews, students from the U.S. mentioned it was a helpful conversational tool in the overseas environment. Jared Jeter, an American NCCU student in the IMPIS program said of his experience: “I’m certain [my American background] has influenced the way I make friends…I feel America's hyper-individualistic society encourages more friendly expressions such as smiling and physical activity.”

Many students surveyed credited a general attitude of openness and friendliness with their success in forming friendships at home and abroad. Mario Haya, a Colombian NCCU student in the IMES program, shared how his country’s culture of extroversion helped him overseas: “I think it’s easy for me to make friends with anybody very quickly, and to generally just be open and talkative, and I attribute a lot of that to my country’s culture. I think it’s also the case for every other Latin American country, not just [Colombia].”

▲IMES Student Mario Haya with NCCU Friends at the Dah Hsian Library

Shared Differences Can Bring Us Together

Across all students and faculty from all countries interviewed, themes of openness to meeting and connecting with people from diverse backgrounds emerged. Cultural differences can complicate friendships, but openness and understanding often bridge the gap.

Professor Deasy Simandjuntak of NCCU said: “I've lived in different countries since [I was a] teenager, and my country's "culture" has not been very influential in how I make friends…First, I'm actually more able to make friends with people from other cultures. Second, if I follow my country's main "culture", then I won't be able to make friends in other countries -- my fellow country[people] tend to keep to themselves whenever abroad, flock together everywhere, and generally won't be able to make rooted relationships with people from other cultures. Third, relationship-making is not based on your original "cultures", but your "habitus", the identity that you absorb from growing up to be who you are, and that can be totally different from the main "culture" of the country where you were born.” In the end, it is not the culture we are born into that defines our ability to build friendships, but rather who we choose to be as a friend.

▲NCCU student friends on a night out in Taipei